By Eric Bonetti, editor.

The Episcopal Church faces a crisis of credibility, with people at all levels increasingly saying there’s a disconnect between what the church says and what it does, especially when it comes to clergy discipline. That gap between rhetoric and reality raises a question: Does anyone have the courage—and stubbornness—to change the status quo within the church? Or is the church so far gone that meaningful change is impossible?

This post explores these issues, including the connection between courage, stubbornness, and reform.

The courage of one’s convictions

For starters, what role does courage play in these issues?

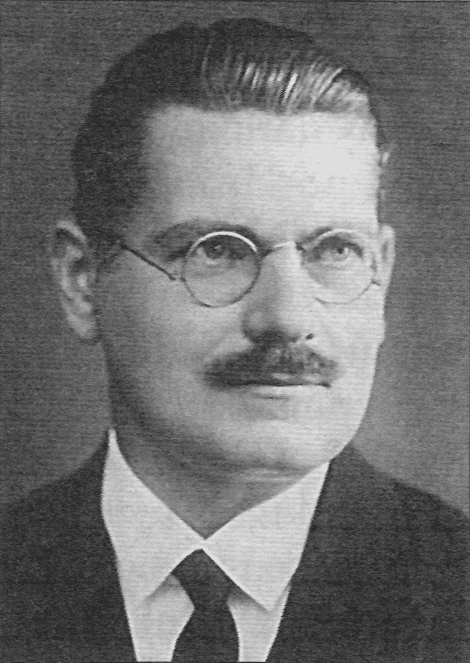

For me, the answer to this and several related questions comes from my great-grandfather, Rudolph Eder, who headed the Baptist Mission to the Balkans prior to World War II.

By all accounts, a courageous and intelligent man, Eder and I wouldn’t agree on much. Both politically and doctrinally conservative, my grandfather had little use for what he termed “innovation” in theology. On the other hand, I am, in some ways, a stereotypical progressive Episcopalian.

Still, he was a kind man and, even more importantly, courageous.

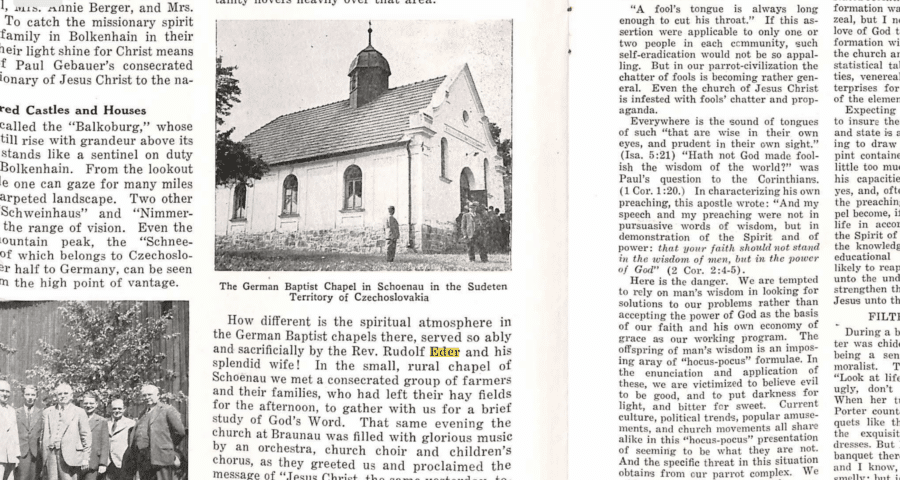

Serving in Schoenau, Czechoslovakia, Eder faced a profound moral problem: The rise of Hitler.

But while many in the mainstream churches preferred appeasement or neutrality, Eder opposed any approach requiring him to make peace with Hitler or Nazism and its structural hatred.

Instead, every Sunday, he preached about the evil of Hitler, despite the row of Gestapo sitting in the back pew of his church, transcribing everything he said and recording everything he did.

And every Sunday, the secret police took Eder into custody, asking questions, including, “What did you mean by ________?”

In every instance, his response was the same, “I believe my words were clear.”

And every Sunday, the follow-up by the Gestapo was the same. Hours of interrogation by the dreaded secret police, followed by a stern warning that if he continued, he would face a horrible fate.

From there, Eder would return home, often to find that his family had been sitting for hours, hungrily eying a now-cold dinner.

When those close to him asked about his intransigence, Eder consistently said, “I can do nothing but preach the Gospel.”

Despite considerable backing from the US and local government officials, my great-grandfather’s rejection of Hitler eventually caught up to him: The German army conscripted him, saying, “This will put a stop to you and your meddling,” before knowingly sending him to a part of the front that was collapsing in the face of Soviet advances.

Eder was, as planned by the Germans, captured by the Russians and disappeared into one of many so-called “silent camps,” or gulags, that the Soviet government never acknowledged.

Other than a brief report from the Red Cross in the late 1950s, which said that he was alive and still being held in the Soviet Union, we never heard from him again. His wife, Annie, died waiting for him at their agreed-upon post-war rendevous point more than 40 years later. But years earlier, she had asked that no one try to find out what happened to her beloved husband until after her death.

This tragic story perhaps explains what many describe as my profound stubbornness, even in the face of daunting opposition.

Of course, no one imagines that my great-grandfather’s opposition brought down Hitler. But he lived a life of courage and integrity despite the terrible price he and others ultimately paid.

Lessons for the Episcopal Church

Eder’s story raises several related questions for the Episcopal Church. As I see it, these questions include:

- Is there a commitment to personal integrity within the denomination?

- Are church leaders and members willing to work for change, even though the cost may be high and the outcome uncertain?

- Does the Episcopal Church prefer, like those who joined the Nazi party, to take the easy way out?

I don’t know the answer to these questions, but if past results are indicative of future performance, my response would be a resounding no.

There’s an added wrinkle to all of this, which is what we see when we scratch the surface.

In the case of the Episcopal Church, once we peel away the sunshine, Chardonnay, and stained glass, things get ugly quickly. Yes, the denomination talks a good game, but behind the scenes, many parishes, dioceses, and other church entities are fraught with conflict and vile behavior.

By contrast, In Eder’s case, his opposition to Nazism went far deeper than many knew.

Indeed, years later, I learned a shocking truth about my great-grandfather. Not only was my family partly Jewish, despite being long-time members of the Church of England, but Eder also had secretly protected many Jews in the area by forging baptismal information in church records. Jewish families, at risk of deportation to the death camps, used these records to convince authorities that they were not, in fact, Jewish.

In other words, to the extent Eder had anything to hide, his secrets were all good ones.

I don’t entirely understand all of this. Was my great-grandfather actually a Christian? Or was he closer to a cultural Jew?

On some level, the theological niceties don’t mean much. The bottom line is that Eder was willing to die for his beliefs, whatever the specifics may have been. And he cared deeply for others, willing to risk death in the concentration camps in order to save Jews.

That contrasts sharply with many Episcopal clergy, who, on the surface, are all smiles, hugs, and winsome words, but underneath are liars, adulters, and narcissists. In other words, whitewashed tombs that look good on the outside, even as the inside reeks of filth and decay. Collectively, these bishops, priests, and deacons are the broods of vipers about which Jesus warned.

The cost of justice

Earlier, we touched on a question that’s intertwined with courage and integrity: being willing to pay the price required to obtain justice. As in, is the denomination, its leaders, and members willing to suffer the consequences that come from doing the right thing?

To hear Episcopalians talk, they would not only be the first to hide Anne Frank but also invite 1,000 of her closest friends to seek shelter in their attics.

But talk is cheap, and evil is banal.

Listen closely to coffee hour at many Episcopal parishes, and one quickly realizes that, when confronted with the chance to save Anne Frank and her family, most churches and their members would more likely instead screw things up:

- They’d gossip about it until even Hitler’s paramour, Eva Brown, far off in Berlin, knew the details, thus pre-empting plans to go into hiding or

- They’d set up a task force on Safety for Jews, study the matter for 20 years, and then decide they couldn’t really do much about the problem or

- They’d push a resolution at the General Convention calling for the safety of Jews, then send a check for $10,000 while developing a Sacred Ground curriculum to study the issue or

- Get mad at the person who actually saved the family on the basis that they didn’t ask the altar guild first about which candles to provide to those in hiding.

But the one thing our Episcopal parish wouldn’t do is to take action. After all, what happens when the Gestapo shows up and confiscates their little slice of stained-glass paradise?

The Episcopal Church faces a crisis of credibility, with people at all levels increasingly saying there’s a disconnect between what the church says and what it does, especially when it comes to clergy discipline. That gap between rhetoric and reality raises a question: Does anyone have the courage—and stubbornness—to change the status quo within the church? Or is the church so far gone that meaningful change is impossible?

This post explores these issues, including the connection between courage, stubbornness, and reform.

The courage of one’s convictions

For starters, what role does courage play in these issues?

For me, the answer to this and several related questions comes from my great-grandfather, Rudolph Eder, who headed the Baptist Mission to the Balkans prior to World War II.

By all accounts, a courageous and intelligent man, Eder and I wouldn’t agree on much. Both politically and doctrinally conservative, my grandfather had little use for what he termed “innovation” in theology.

Still, he was a kind man and, even more importantly, courageous.

Serving in Schoenau, Czechoslovakia, Eder faced a profound moral problem: The rise of Hitler.

But while many in the mainstream churches preferred appeasement or neutrality, Eder opposed either approach.

Instead, every Sunday, he preached about the evil of Hitler, doing so despite the row of Gestapo sitting in the back pew of his church. And every Sunday, the secret police took Eder into custody, asking questions, including, “What did you mean by ________?”

In every instance, his response was the same, “I believe my words were clear.”

And every Sunday, the routine was the same. Hours of interrogation by the dreaded secret police, followed by a stern warning that if he continued, he would face a horrible fate.

From there, Eder would return home, often to find that his family had been sitting for hours, hungrily eying a now-cold dinner.

When those close to him asked about his intransigence, Eder consistently said, “I can do nothing but preach the Gospel.”

Despite considerable backing from the US and local government officials, my great-grandfather’s rejection of Hitler eventually caught up to him: The German army conscripted him, saying, “This will put a stop to you and your meddling,” before knowingly sending him to a part of the front that was collapsing in the face of Soviet advances.

Eder was, as planned by the Germans, captured by the Russians and disappeared into one of many so-called “silent camps,” or gulags, that the Soviet government never acknowledged.

Other than a brief report from the Red Cross in the late 1950s, my family never heard from him again. His wife, Annie, died waiting for him at their agreed-upon post-war rendevous point more than 40 years later. But years earlier, she had asked that no one try to find out what happened to her beloved husband until after her death.

Today, details are scant, but we believe Eder died about 20 years later, still held by the Soviets.

This tragic story perhaps explains what many describe as my profound stubbornness, even in the face of daunting opposition.

Of course, no one imagines that my great-grandfather’s opposition brought down Hitler. But he lived a life of courage and integrity despite the terrible price he and others ultimately paid.

Lessons for the Episcopal Church

Eder’s story raises several questions for the Episcopal Church. As I see it, these questions include:

- Is there a commitment to personal integrity within the denomination?

- Are church leaders and members willing to work for change, even though the cost may be high and the outcome uncertain?

- Will the Episcopal Church, like those who joined the Nazi party, take the easy way out versus addressing its existential issues?

I don’t know the answer to these questions, but if past results are indicative of future performance, my response would be a resounding no.

There’s an added wrinkle to all of this, which is what we see when we scratch the surface.

In the case of the Episcopal Church, once we peel away the sunshine, Chardonnay, and stained glass, things get ugly quickly. Yes, the denomination talks a good game, but behind the scenes, many parishes, dioceses, and other church entities are fraught with conflict and vile behavior. Even worse, Episcopalians often lack the introspection to recognize that these behaviors are not normative in different denominations.

In Eder’s case, his opposition to Nazism went far deeper than many knew.

Indeed, years later, I learned a shocking truth about my great-grandfather. Not only was my family partly Jewish, despite being long-time members of the Church of England, but he had secretly protected many Jews in the area by forging baptismal information in church records. Jewish families, at risk of deportation to the death camps, used these records to convince authorities that they were not, in fact, Jewish.

In other words, to the extent Eder had anything to hide, his secrets were all good ones.

That contrasts sharply with many Episcopal clergy, who, on the surface, are all smiles, hugs, and winsome words, but underneath are liars, adulters, and narcissists.

In other words, these clergy are whitewashed tombs that look good on the outside, even as the inside reeks of filth and decay. Collectively, these clerics are the broods of vipers about which Jesus warned.

The cost of justice

His religious convictions caused Eder’s capture and death at the hands of the Soviets. That raises the question: Are Episcopalians willing to pay the price to reform the church?

To hear Episcopalians talk, they would not only be the first to hide Anne Frank but also invite 1,000 of her closest friends to seek shelter in their attics.

But talk is cheap, and evil is banal.

Listen closely to coffee hour at many Episcopal parishes, and one quickly realizes that, when confronted with the chance to save Anne Frank and her family, most churches would more likely instead screw things up in one of several ways:

- They’d gossip about it until even Hitler’s paramour, Eva Brown, far off in Berlin, knew the details, thus pre-empting any possibility of hiding.

- They’d set up a task force on Safety for Jews, study the matter for 20 years, and then decide they couldn’t really do much about the problem.

- They’d push a resolution at the General Convention calling for the safety of Jews, then send a check for $10,000 while developing a Sacred Ground curriculum to learn about the issue.

- Get mad at the person who actually saved the family on the basis that they didn’t ask the altar guild first about which candles to provide to those in hiding.

But the one thing most Episcopal parishes wouldn’t do is to take action. After all, what happens when the Gestapo shows up, arrests people, and confiscates their little slice of stained-glass paradise?

In real life, that’s exactly what happened to Eder’s church, although the collapse of the German front meant that it was the Soviets, not the Germans, who seized the property.

Subsequently, the church housed a sailors’ club, then stood completely abandoned with barred windows. The authorities designated it a warehouse, and finally, it served as a teachers’ house. Meanwhile, believers met secretly in homes for the next 30 years before the Soviet Union recognized the church in 1977.

Of course, this sort of steely determination is often the province of evangelical churches. Mainline churches instead typically cooperate with evil, ignore it, or acknowledge it but say they don’t want to get involved.

There also is a definitional aspect to this challenge for mainline churches.

Faced with a comfortable existence, the Episcopal Church and others define “hardship” as having to give up a few hours a week to volunteer at their church or increase their pledge by $50 a month.

But tell an Episcopalian that they have to give up vacation next summer, and they will look at you like you just grew a third eyeball. And forget possible imprisonment and death; it’s not even on the radar.

Nor are Episcopal judicatories any better. Much like the sea of complicity surrounding the Smyth and Peter Ball scandals in the Church of England, the priority for the Episcopal Church often is protecting the organization rather than living out the Gospel.

Today, we look at incoming Presiding Bishop Sean Rowe’s stated desire to forge one church with a discerning eye.

Indeed, as things stand, the Episcopal Church is an amalgamation of shape-shifters. It is congregational in polity when clergy discipline is involved but hierarchical when it comes to real and personal property.

Thus, the church is an example of organizational narcissism at its worst, in which the ends justify the means, and integrity means not rocking the boat.

Moreover, if I take a step back, I see a denomination with broken governance, frantically trying to reach non-existent strategic objectives.

In other words, the denomination today is dysfunctional on all levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal, governance, and organizational.

Looking into the future

So, assuming the Episcopal Church grows a backbone, sets up a workable governance structure, and establishes meaningful strategic goals, will positive change result?

I hope so, but it’s hard not to be dubious.

After all, culture triumphs over policies and procedures every time. That’s the one great lesson of change management.

Today, the Episcopal Church reminds me of a hospital patient with advanced sepsis. The sepsis creates a life-threatening emergency and requires urgent treatment, but there’s an underlying question: Have the patient’s organs begun to fail?

If the answer is yes, the patient has reached a tipping point where the decline is irreversible, and further treatment is futile. But until we know the answer, it’s all hands on deck to save the patient’s life.

I’m also aware that many, myself included, have warned for years that the church is lurching toward an existential crisis. But now, for the first time in recent history, the church’s inflation-adjusted income is declining.

And we face a grim reality: The church’s demographics are much older than that of the population at large. Indeed, more than a third of current members will die within the next 20 years.

Layered on top is yet another inconvenient truth, which is that many Episcopalians aren’t leaving through natural attrition. Indeed, the recent results from the 2022-2023 parochial reports reveal that, while Sunday attendance has somewhat bounced back from pandemic-era levels, funerals have declined by almost 5 percent during the past decade.

In other words, at a time when large swaths of the church are dying off, many are hitting the bricks under their own power, versus being carried off in a hearse.

And while we see some growth in baptisms, continuing declines in weddings suggest that, by the time people reach adulthood, they’re not seeing any reason to remain involved in the church. That’s damning, because young people are both the future of the church — and remarkably adept at sniffing out hypocrisy.

Rounding out these problems is the church’s glacial pace and seeming inability to recognize how slowly it moves when compared to other organizations.

For example, a for-profit company would typically deal with a complaint of sexual harassment/retaliation within hours or, at most, a couple of days. Yet the Title IV complaints against Dallas Bishop George Sumner, which we previously reported, have languished for more than a year a the national church without even being acknowledged.

The icing on the cake is the church’s inability to assess the seriousness of issues.

To use the Sumner case above, sexual harrassment is, in for-profit companies, normally grounds for immediate termination. Yet in the Episcopal Church — which should be safer than a for-profit — there is no sense that the matter is urgent. The result, not surprisingly, is that sexual harassment often is treated as de facto a relatively minor issue. That in turn further traumatizes victims.

In other words, even if the Episcopal Church gets its act together, it faces a series of almost insurmountable hurdles caused by both its own dysfunction and the passing of the Baby Boom. And because judicatories evaluate many situations in the context of the church’s current dysfunction, they fail to recognize the underlying problems.

Consider: Where else can an organization say, with no sense of irony, that complaints involving the misconduct of employees should be resolved within 15 months? Yet that is exactly what General Convention discussed last time it met when it considered legislation that Title IV cases should — please and pretty please — be resolved withing 15 months whenever possible.

Beyond hope?

That’s not to say that the Episcopal Church is beyond hope.

Indeed, we’ve been here before, including in the years immediately following the American revolution, when the church was disestablished, and assets seized and sold. Yet despite the collapse of the church as it was then known, the Episcopal Church regrouped and, at times, thrived.

One final note: Episcopal clergy like to talk about how this is a resurrection moment. To that I say: Stop. Just stop.

Resurrection first requires death. On that score, I can say with certainty that dysfunction in the church is far from dead.

In fact, the toxic aspects of the denomination are alive and well and, despite having been around for decades, show no signs of slowing down or getting long in the tooth.

Let’s hope the denominattion is finally ready to take its challenges seriously.

Leave a Reply