“The reason why offenders get away with what they do is because we have too many cultures of silence. When something does surface, all too often the church leadership quiets it down. Because they’re concerned about reputation: ‘This could harm the name of Jesus, so let’s just take care of it internally.’ Jesus doesn’t need your reputation! When somebody says that, it’s a lie. Keeping things in the dark and allowing souls to be destroyed by abuse, that shames the Gospel. Jesus is all about transparency.” Boz Tchividjian, grandson of Billy Graham and President of G.R.A.C.E.

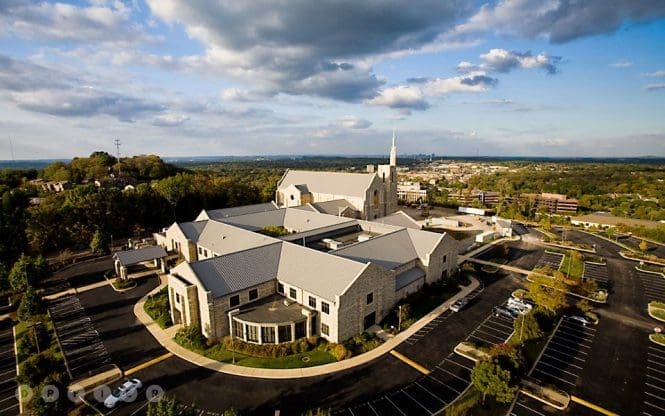

On a picturesque hill in southern Nashville, Tennessee, a knoll the old-timers named Red Bud Hill, sits a beautiful building called Covenant Presbyterian Church (PCA). On weekends, hundreds of people gather for worship services at this facility, one of the leading PCA churches in the south. Throughout the week the building is occupied by the staff, faculty and students of The Covenant School. The land around the church and school once belonged to the family of Amy Grant (the Burtons), but it is best known as the location where Union forces amassed to stop the advancing Confederate army during the last major Confederate offensive of the Civil War. This December 15-16, 1864 Civil War battle is called by historians The Battle of Nashville.

On a picturesque hill in southern Nashville, Tennessee, a knoll the old-timers named Red Bud Hill, sits a beautiful building called Covenant Presbyterian Church (PCA). On weekends, hundreds of people gather for worship services at this facility, one of the leading PCA churches in the south. Throughout the week the building is occupied by the staff, faculty and students of The Covenant School. The land around the church and school once belonged to the family of Amy Grant (the Burtons), but it is best known as the location where Union forces amassed to stop the advancing Confederate army during the last major Confederate offensive of the Civil War. This December 15-16, 1864 Civil War battle is called by historians The Battle of Nashville.Today, Red Bud Hill is the location of another battle of Nashville.

The modern skirmish, unlike its predecessor, is being fought in the courtroom and not the countryside. The legal battle is being discussed with hushed tones in the tony parlors of homes in Belle Meade, Brentwood, Franklin, and other Nashville suburbs. The fight has led to verbal sparring in the classrooms and hallways of the prestigious girls school, Harpeth Hall, as well as other private schools in Nashville. The interesting twist to this particular civil case is the allegation that wealthy and influential Covenant Presbyterian Church leaders “unlawfully intimidated” Austin Davis and his family. Specifically, the allegation is that in 2008 Covenant Presbyterian church officials sought to intentionally ruin Mr. Davis’ good name and reputation by falsely accusing him of being ‘mentally unbalanced,’ telling civil authorities, members of the congregation, and others that he was “a security concern” and was “threatening to bring harm to the congregation or its members by use of force, including but not limited to guns.” This slander, according to the allegation, was designed to discredit Austin Davis and to allow church officials to conceal from public view the “heinous and repetitive” sexual molestations of a minor by one of the church’s officers (see Complaints 18-24).

| Attorney Duncan Cave |

This court battle, waged by attorney Duncan Cave, has received very little attention nationally, and surprisingly, none from the Nashville media as of yet. Some of the same people involved in the investigation and prosecution of the infamous Vanderbilt rape case and the murder investigation of Steve McNair are part of this modern day battle which has affected the lives of many people, particularly Austin Davis, his wife Catherine, and their two teenage children, Daisy and Drew. Austin Davis has gone from a deacon and chairman of the Mercy Committee at Covenant Presbyterian Church and the man who designed the Covenant School logo, insisting the Latin phrase Veritas Christo et Ecclesia (“Truth for Christ and the Church”) be included, to a man now persona-non-grata at Covenant Presbyterian Church, alleged by Covenant Presbyterian Church officers to be ‘mentally unstable’ and a ‘potential shooter,’ and talked about by those influential leaders in the church with disgust and disdain.

This is no ordinary church conflict. My purpose in writing is to familiarize the reader with Austin Davis and his family, and to encourage people to review the appropriate data and records, and to refrain from making a judgment against Austin Davis or Covenant Presbyterian without performing personal due diligence.

|

| Austin Davis at Covenant (May 2014) |

Austin Davis grew up in Natchez, Mississippi where his grandfather worked as a dairy farmer. “My grandfather was the closet example to Christ I will ever see on this planet,” Austin says. His father, a Korean War veteran, was “the toughest, most fearless man I ever new, but he thought Christians were spineless and too afraid to stand up for what they believed.” Austin’s mother taught him the gospel when he was a boy and Austin received Christ as his Savior at a young age. “My dad would often tell me he had been to ‘hell and back’ and that he could never believe in a God that was so unjust and cruel.” However, years later, after intense and often difficult dialogue with his father, Austin would eventually guide his father (age 70) to faith in Christ just a year before his death in 2002. In 1961 Austin’s father was accepted to Vanderbilt University, earning an Atomic Energy Commission scholarship for his masters in physics. Mr. Davis moved his family from Natchez to Nashville, where Austin spent most of his early school years. After graduation, Austin’s father worked for IBM in Nashville. Later, he was transferred to New Orleans and moved his family to the Big Easy for a couple of years. Then IBM transferred Austin’s father to Memphis, Tennessee where Austin attended his senior year of high school at the prestigious all boys Memphis University School. The instructors and classmates at Memphis University School drilled into Austin the school’s legendary ‘honor code,” reinforcing the principles his own father had taught him over the years at home. Austin graduated from Memphis University School in 1973 and went to play baseball for the University of Mississippi. However, his dream (Austin would call it his ‘impossible dream’) of playing baseball for former Yankee player and then current baseball coach at Ole Miss, Jake Gibbs, ended his freshman year with an eye injury while in the batting cage. Austin would go on to graduate from Ole Miss with a degree in business.

After graduation from college, Austin Davis went back to Memphis to work on writing his first novel rather than going to law school. Austin loved reading and history and had a desire to make writing his career. It was during this time that he met the great Civil War historian Shelby Foote and the two became life-long friends. Though Shelby was a declared agnostic, Austin would enter into deep conversations about God with Shelby, especially toward the end of his life. “I was blessed to be his friend and to pray with him all the way to the bitter end, including in the critical care unit, as Shelby laid down his weapons to end his ‘war’ with God and came to peace with the Almighty.” It was Shelby Foote who taught Austin never to throw away any document, letter, or other evidentiary material and to record everything with the meticulous note keeping and documentation of a historian. That training would serve well Austin Davis later in life.

| Austin and Catherine Davis, Daisy and Drew (2000) |

After writing his first novel, Austin entered the business world and moved in the early 1980’s to Nashville, where his father and mother had also relocated. Austin would meet his future wife, Catherine Fleming, while the two were seated near each other on the back row during a Sunday morning worship service. Catherine’s father, Dr. James Fleming, was a well-known plastic surgeon in Nashville. The Flemings were close family friends with the Tennessee Gore family. Al and Tipper Gore would often babysit Catherine when she was a little girl, and Al’s very first campaign fundraiser was held in the living room of the Fleming family home in Bell Meade. Austin Davis and Catherine Fleming would be married in 1992 at Covenant Presbyterian. Austin was 36. Catherine was 30. It was the first marriage for both. The young couple loved Covenant Presbyterian, the pastoral staff, and the ministries of the growing church. It was the practice of Catherine to invite strangers and new acquaintances from all walks of life to church on Sundays, and in many instances, she would pick them up and bring them herself, taking her guests out for lunch after church. On occasion, Catherine would send Austin to pick up former Senator Al Gore, Sr. and his wife Pauline and bring them to Covenant Presbyterian, an act of kindness for a loving relationship for the Gores that had received Secret Service clearance for Austin and his entire family. Austin and Catherine had deep roots in Nashville and throughout the state of Tennessee and a love for people in general.

| George Digby, Austin, and the Digby Vols |

In 1995 Catherine Davis gave birth to a daughter named Daisy, and a little over three years later she gave birth to a son named Drew. Austin worked hard to provide for his wife and two kids financially, but he was always active and involved in his kids lives, including coaching his son’s all-star summer baseball team, which won the Tennessee state championship in 2011. During a chance meeting in a restaurant in Nashville, Austin met the legendary Boston Red Sox scout George Digby who was in his 90’s and living in Nashville. Austin would become a very close friend with George until his death on May 3, 2014. George Digby was tickled pink when Coach Austin and his son Drew named their team “The Digby Vols”in honor of him. In addition to coaching his son’s baseball team, Austin filled in as athletic director for a year at the prestigious Ensworth School when the school’s beloved athletic director battled brain cancer.

| Pastor Jim Bachmann |

The Austin Davis family attended Covenant Presbyterian faithfully during the 1990’s and 2000’s and participated in all church activities. Austin became close personal friends with Jim Bachmann, the Senior Pastor of Covenant. Jim had moved from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Nashville in order to become the Senior Pastor of Covenant Presbyterian in 1991, the same year Austin began attending the church. Austin and Catherine made many other friends within Covenant during the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Austin joined the men’s church softball team and Catherine participated in the women’s ministries. Austin was elected by the church to serve as an officer of Covenant, becoming a member of the Diaconate. By 2000 the Diaconate had appointed Austin Davis to be Chairman of Covenant’s Mercy Committee, bearing the responsibility of helping church members in distress or need. The church continued to grow, and plans were soon made to build a $18 million dollar Gothic sanctuary on top of Red Bud Hill.

In 2002 Austin Davis, in his role as Chairman of Covenant’s Mercy Committee and an officer of the church, began to question church leaders as to why The Book of Church Order was not being followed in the discipline of a church member named Greg Lurie. Austin believed that following the church approved rules and procedures provided checks and balances for church power. Without them, church leaders had the unchecked ability and means to destroy a person’s life, particularly when church leaders desired to protect the reputation of another church leader and/or his family.

Favoritism, Cronyism, and the Book of Church Order

| Greg Lurie |

Greg Lurie joined Covenant Presbyterian by profession of faith in late 1993. Greg’s background was in accounting and he served as the Director of Finance for Belmont University (1999-2002), and later held various positions in the accounting offices of Lipscomb University, Fisk University and served as a consultant to national corporations. After joining Covenant in 1993, Greg married the daughter of a Covenant elder in a ceremony performed by Pastor Jim Bachmann during the September 24, 1995 Sunday morning worship service. It was the second marriage for both Greg and his new wife, and they each brought children into the union. Over the next five years Greg’s new wife would give birth to four additional children and experience two miscarriages. After the birth of their fourth child, Greg’s wife went to work at Covenant Presbyterian in the early childhood development department. Due to the pressures of a blended family, work, and other personal struggles in both Greg and his wife, conflict began to arise within the Lurie marriage. In the fall of 2000, the Luries reached out to the pastors of Covenant Presbyterian for counseling and support.

On Friday, March 1, 2002 Greg and his wife were involved in a marital dispute in the parking lot of Bellevue Center Mall. There is disagreement between the two parties as to what actually occurred, but after the pastoral staff discussed the event with Greg’s wife and Greg’s father-in-law, Covenant Presbyterian pastors decided to take Greg Lurie’s four small children away from him, without his knowledge, and place them in what the pastors told Greg much later was ‘a safe house.’ Greg was told that Saturday he and his wife needed a cooling off period. Then, on the following Sunday, March 3, 2002, with Greg’s two older children from his first marriage sitting with him in their customary spot on the second row of Covenant Presbyterian, communion was not given to Greg, to his 12-year old son or to his 9-year-old daughter by the elder assigned to his row. The elder happened to be Greg’s father-in-law. The refusal to serve communion at Covenant is the consequence of excommunication from the church. Greg was confused. Was he being excommunicated? Were his kids from his first marriage no longer deemed ‘worthy’ of communion since they had received it before? Had the church judged him and tried him regarding his marriage and the marital dispute on Friday night without hearing from him?

Greg Lurie Appeals to the Nashville Presbytery

That afternoon, Sunday, March 3, 2002, Greg Lurie wrote an email to the Presbyterian Church of America requesting their denominational help. Greg felt that Covenant Presbyterian’s pastoral staff and elders were making unilateral decisions about him without hearing from him, not to mention these decisions were being based on erroneous information and false assumptions given to them by his wife and her father. Because Greg’s father-in-law was an elder and friends with the other men in the Session, Greg felt that his side was not even being heard. Unbeknown to Greg at the time, that Sunday morning in church, church leaders came to Catherine Davis’s classroom where she taught the five-year-old Sunday School class and told Catherine that if Greg Lurie came to pick up his daughter, Catherine was not to give the child to her father under any circumstances. “I was a little shaken by what I heard,” said Catherine. “I went home and asked Austin, ‘What has Greg Lurie done?'” Austin felt it was his responsibility, as Chairman of the Mercy Committee, to find out what was going on within the Greg Lurie family. It would be more than a week later before he had a chance to talk to Greg.

By that time, Greg was not in the mood to visit with anyone from Covenant. From Friday, March 1, 2002 to Friday, March 8, 2002, Covenant Presbyterian pastors and elders, according to Greg Lurie, “had steamrolled me.” When Austin entered the picture in the middle of March 2002 to try to help Greg restore his marriage, he went to Greg and later to his wife as an officer of Covenant, fulfilling his role and responsibility as Chairman of the Mercy Committee and deacon of Covenant Presbyterian.

“At the time I didn’t know much of what was going on.” says Austin, “I wasn’t sure whether or not to believe what the pastoral staff and elders were saying about Greg. Greg definitely was not sure whether or not he could trust me, because I was an official from the church. However, after visiting and helping Greg over the course of several months, I developed two serious concerns with our church pastors and Session over how Greg’s situation had been handled: (1). First, the Book of Church Order had not been followed. Why was process not given to Greg, a member of Covenant? (2). Second, Greg’s own children were taken from him without his direct knowledge as to where they were or how long they would be away. It was sometime later when Greg was finally told they had been taken to “a safe house,” the home of another officer of Covenant. How could pastors have this kind of ‘authority’ over a man’s family? I was concerned for this man’s young children. I wanted some answers. When I first began to ask questions, I was told by one of the elders and a pastor of the church, ‘Austin, don’t stick your nose in this business unless you’ve been called to it.’ That made me think through my calling. I had been called. It was my responsibility to ‘care for the flock” as a deacon. I learned as a boy that honor was more important than reputation. The honorable thing to do was to ask the questions that needed asking, regardless of the rich and powerful people who wanted me to shut up. For the next four years I kept asking the questions that nobody seemed to want to answer.”

Greg Lurie’s marriage was never able to be reconciled, and the divorce was finalized on March 31, 2004. Austin Davis continued to ask his questions, moving from asking them verbally during private committee meetings to placing his concerns in writing to other officers of the church. To get a sense of the humble and respectful spirit Austin Davis displayed as he voiced his questions and concerns about process in dealing with members to the Covenant Presbyterian’s pastors and elders, you can read Austin’s December 3, 2003 letter to them. Less than a month later, on December 31, 2003, Austin writes a detailed and well-reasoned letter appealing to Covenant Presbyterian’s Session to follow the Book of Church Order. Greg Lurie, through the encouragement of Austin Davis, continued to attend Covenant Presbyterian throughout 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006. When Austin Davis heard that Covenant was possibly removing Greg from the church rolls on December 31, 2004 for alleged non-attendance, Austin wrote another letter dated December 3, 2004, asking Covenant’s church officers to again to follow the Book of Church Order and not play favorites with members.

Austin Davis’ Continuing Concerns with Covenant Presbyterian

In 2005, Austin exchanged letters with the Covenant pastor who had counseled Greg Lurie and his wife, attempting to express his concerns that the emphasis of Covenant’s pastoral counsel with couples facing marital difficulty should be restoration, not divorce. Because the Lurie divorce had been finalized by 2005, Austin’s letters expressed his general concerns with the number of divorces at Covenant and the pastoral response to them, and the letters were written by hand, sent to one pastor only. In response, the Covenant pastor gave Austin’s letters to the Session (pg. 3) and then wrote Austin saying, “Your problem Austin is not with me. It is with the entire session and pastoral staff. We stand united…”

Austin felt that his only chance of correcting the problem of Covenant Presbyterian skirting the Book of Church Order in Greg Lurie’s case, not to mention future cases, leading to the Session showing favoritism to certain members, was for Austin to address the entire church body regarding his concerns. For nearly four years, Austin had written only to the Covenant Presbyterian officers and pastors in his role as a fellow officer of the church, but by 2005/2006 he determined the church needed to hear from him directly regarding the issues. Not surprisingly, his requests to personally speak to the congregation were refused. After again reading the Book of Church Order, Austin had an idea. He offered his resignation as a deacon of Covenant Presbyterian in May of 2006, believing that the Book of Church Order gave a resigning officer the right to address the church regarding the reasons for his resignation. However, after offering to resign his position as a Covenant officer, his request to address the church was still denied. Finding all avenues closed to resolve what Austin believed to be a serious matter within his church, Austin wrote a letter dated June 9, 2006, to the Nashville Presbytery, requesting that they “investigate serious offenses of the pastors and Session … of the church I dearly love.” The following Sunday, the Covenant pastor involved with the Greg Lurie counseling “aggressively engaged” Austin Davis and his family in response to Austin’s letter to the Presbytery. Just a few days later a church ‘court’ determined that Austin needed to repent for causing “considerable pain and unrest…to the congregation of Covenant.”

| Austin, Drew, Catherine and Daisy Davis (May 2014) |

Finally, after four years of attempting to get the Covenant Presbyterian pastors and Session to follow the Book of Church Order and to avoid favoritism, cronyism and partiality among its members, the Austin Davis family resigned from membership at Covenant in a letter dated July 26, 2006, and Austin resigned as an officer of the church. Austin Davis and his family were leaving the church they loved. They kept the details of their concerns regarding Covenant Presbyterian discreet, and would leave the church without making those details known to everybody. Ironically, just days after he resigned, Austin heard that the Session had been deliberating formal ‘discipline charges’ against him for ‘sowing discord.’ In response, Austin wrote a letter to the Session in September 2006 requesting reinstatement to the church, believing that the implementation of ‘process’ (formal discipline charges) against him would allow him to finally voice his concerns regarding the leadership of Covenant in a public forum. Austin’s request for reinstatement was denied.

For several months the Davis’ family did not attend Covenant Presbyterian. Then, a few Covenant friends and an Ethiopian evangelical minister began to encourage the Davis’ family to reconcile with the leadership of Covenant. Close friends knew that there were problems with the leadership, but they didn’t know all the specifics. All they did know was the Davis family was being missed at church. They urged true Christian reconciliation. With so many friends at Covenant, and with no desire to be in leadership again, Austin Davis followed the advice and encouragement of his friends and wrote an ‘apology’ to the Session. Austin wrote it in March of 2007 and some time during the summer of 2007, Austin and his family began attending Covenant again. In August 2007, the Covenant pastor who had been most intimately involved in the Greg Lurie divorce took a new position in a PCA church in Chicago. (Note: This former Covenant Presbyterian pastor had a relationship with a woman that was not his wife while in Chicago and is no longer with the church). After the pastor left Covenant, and after the Davis family had been faithfully attending for several months, Austin requested readmission to membership for himself and his family in a letter dated November 27, 2007. The Session denied Austin’s request in a response that is dated November 29, 2007, a letter signed by the clerk of Covenant Presbyterian’s Session and containing the following statement to Austin:

“We encourage you to pursue membership in a church whose leadership you can trust and follow.”

However, Austin Davis and his family continued to attend Covenant as they had done since 1992, the year of their marriage. A Covenant friend of Austin reached out again to the Session of Covenant Presbyterian in January of 2008, proposing a resolution whereby the women of the Davis family could be readmitted to Covenant Presbyterian as members provided Austin would agree to the following statement:

“Membership is reinstated if I do not pursue this matter (an investigation of Covenant leadership) with the Presbytery, and once membership is granted I will not challenge, fight or dissent with leadership again.”

Austin Davis AGREED to those terms. That shows Austin had no vendetta and just wanted to get back to worshipping at the church where he had been a member for over 15 years. However, a wise Covenant pastor who himself later left Covenant Presbyterian over disputes with leadership, refused to allow Austin to sign the agreement because of the phrase the Session insisted Austin sign- “Once membership is granted I will not challenge…or dissent with leadership again.” That pastor wisely felt for Austin to agree to such a statement would be foolish. The pastor told Austin, “You can’t sign this because no Christian should bind his conscience.”

A Dark Secret at Covenant Presbyterian

In the summer of 2007, a youth worker at Covenant Presbyterian was told by a high school junior-to-be that she had been repeatedly sexually molested by her adopted father when she was a young girl. This youth worker reported the allegations of abuse to a pastor at Covenant Presbyterian and confirms that pastoral staff at Covenant knew of the abuse allegations in 2007. For several months the adopted father of the girl, a man who happened to be a church officer at Covenant and the owner of ‘the safe house’ where the pastors placed the four children of Greg Lurie in the spring of 2002 without Greg Lurie’s knowledge, repeatedly denied that he had sexually molested his minor adopted daughter.

However, at some point in early 2008, around the time Austin Davis was willing ‘for the sake of peace’ to sign a statement that he would “never challenge … or dissent with (Covenant Presbyterian) leadership again,” the father of the girl ‘confessed’ to church officers his acts of child molestation. The confessed child molester was assisted by Covenant leadership to enter a sexual treatment clinic. Upon arriving back home from treatment, the wife of the confessed child molester filed for separation. Nearly a year later, on March 13, 2009, the wife of the confessed child abuser filed for divorce, giving one of the reasons for the filing as:

“The past acts of abuse and molestation of the parties’ minor child.” (Allegation #8)

Ironically, in the summer of 2007, the same summer when Covenant leadership became aware of the allegations of molestation against one of their church officers, I stepped to the microphone at the Southern Baptist Convention and made a motion that …

“A database be developed containing the names of all Southern Baptist ministers who have been credibly accused of, personally confessed to, or legally been convicted of sexual harassment or abuse, and that such a database be accessible to Southern Baptist churches.”

Though I am not a Presbyterian, my motion was rooted in the knowledge that there is a tendency within religious denominations to ‘conceal and cover’ sexual abuse by church officers and ministers out of concern for the “reputation” of the church. TIME Magazine declared that the failure of my motion was ‘one of the Top 10 most underreported stories in the nation that year.’

When the church officer at Covenant Presbyterian ‘confessed’ to his molestations in the spring of 2008, there seems to have been no effort by Covenant Presbyterian leadership to ‘make known’ or ‘reveal’ the sins of their church officer. There is no police report. There is no public record. There are no discovered church court minutes recording his sins. The Tennessee Department of Child Services, the Davidson County District Attorney’s Office, the Tennessee Attorney General’s Office, and other civil authorities can produce no record that they were ever notified by the Covenant Session in 2007, 2008, 2009, or 2010 of the child molestations.

In addition, the child molester continued to attend Covenant Presbyterian without notification of the church body of his confessed actions, meaning there were no boundaries in place to protect children.

What does happen at Covenant Presbyterian Church after the confession of the child molester in April 2008 to July 2008 seems shocking, and it forms the basis for the lawsuit by Austin Davis against Covenant Presbyterian the Nashville Presbytery and the National PCA.

“If the facts and evidence supporting my letters are uprightly determined to be untrue by the leadership of Covenant, I call for Pastor Jim Bachmann to publicly declare the letters to be a lie to safeguard the Lord’s Commonwealth which he has vowed to shepherd and protect.

If the facts and evidence supporting my letters are uprightly determined to be true by the leadership of Covenant, I call for immediate public repentance, restitution, and reconciliation to the glory of Christ and His Church.

This next Sunday would be an appropriate time for six years of lies and slander to come to an end.”

This just became absurdly relevant.

And sadly so. Our hearts break for all those affected by the shooting, and prior misconduct at Covenant.

Why is John Perry, the confessed child molester not named in this piece? There are questions about the time period he was molesting children and the shooter was a child at the Covenant school, where he had access to the students as well as keeping them in a building in the back of his house – the so-called safe house.

That’s an excellent question. The original article was republished from fellow blogger Wade Burleson. We are trying very hard to get details from the Nashville police, which are trying to stiff us at every turn. But the reports that the shooter had a conflictive home life, a tendency towards infantilism, and several other hints make us deeply suspicious that she was placed in John Perry’s so-called safe house.

And we’re very troubled that Covenant has not come clean about its treatment of Austin Davis and his family. That includes retaliation in which the church tried claiming that Austin might be dangerous, etc. And they were aided and abetted by the Nashville police department. People who have the courage to speak out when children are at risk should be applauded, not penalized.

Unfortunately, we also haven’t been able to reconnect with Austin, who is a really great guy. Stubborn, maybe, but he has integrity and we like him tremendously. We think he also was very hurt when some media outlets named his daughter Daisy as the shooter. She definitely had no role in the matter.

Please keep your fingers crossed that the police department will approach this matter with integrity. It is essential that the truth come out in full—whatever that may be. And the church needs to come clean about its sins and make things right with Davis. Right now, he is an outcast, but he should be considered a hero.

BTW, thank you for taking a stand on behalf of kids. Far too many just shrug when issues like this come up. We need the truth.

Could Austin Davis have reported the molester?

He did, and faced egregious retaliation. Covenant knowingly took language out of context, went to the police, and claimed that Austin was a threat. This is a horiffic abuse of power, and we continue to urge Covenant and the Nashville police department to come clean, make restitution, and change their ways. And we’re not buying the whole idea that it’s water over the dam. Austin’s a good guy, and his life has been made a living hell by Covenant. Of course, that doesn’t justify violence, but the church has got to fix this situation.

To answer Hoo Wee’s question:

In 2014, the information I shared was in the hands of proper authorities. I never intended to investigate allegations of criminal conduct, only to defend the man who reported them. Sadly, circumstances in 2023 and imminent court proceedings may cause the mainstream media, the District Attorney’s office, investigators for Child Services, and the NPD to do what many (including me) believe should have been done a decade ago.

Is that (impending legal proceedings) why the links to the emails have been restricted? Was trying to read them, but notice that access has been revoked.

Hello Chaplain. I think the original links were owned by a third party, who later changed the links. While we have not been able to update all of them, Wade’s original article is well worth reading, even now.