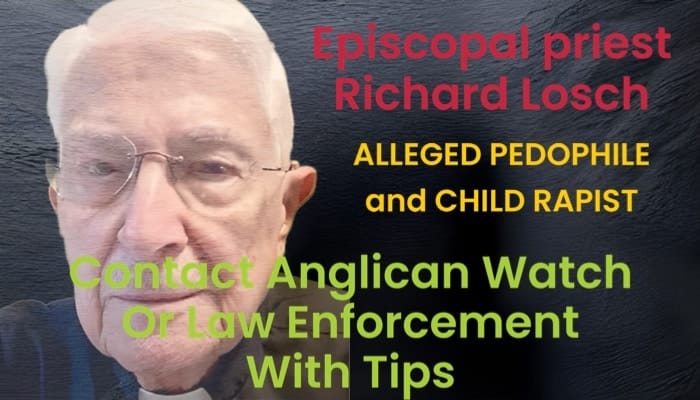

A New Hampshire criminal trial of Episcopal priest Richard Losch ended earlier today in a mistrial due to a hung jury. Losch was previously indicted for the rape of a boy in the mid 1970s.

The news follows the court’s refusal to allow into evidence allegations that Losch sexually groomed the victim, encouraging him and other boys to go skinny dipping. (Indeed, a year prior, Losch told students that showering with the Scouts was preferable to showering with adults. He also showered with the victim and a group of other boys, the only adult in the shower. Need we say more?) The court did so on the basis that these were “prior bad acts,” versus the correct approach, which is to regard them as an integral part of the alleged crime at hand, child sexual abuse.

Additionally, defense counsel for Losch, Michael Iacopino, made a series of ethically questionable claims during the trial, including that the victim, known by the pseudonym “Jack,”:

- Was motivated by a desire for fame and fortune, despite the victim’s request to remain anonymous.

- Sought money, despite the fact that the Boy Scouts have provided only nominal financial assistance to the victim – and by nominal, we mean de minimus.

- Was motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment — despite the fact that “Jack” was born and raised in the Catholic faith, and has never made anti-Catholic statements.

- Was motivated by political perspective.

- Was egged on by this and other “priest abuse” publications. This is a fabrication, as “Jack” began pursuing the issue long before being in contact with Anglican Watch.

Additionally, defense counsel falsely told the jury that Losch had been cleared by the Episcopal Church of wrongdoing. This is an outrageous fabrication and shocking to the conscience, as the Diocese of Alabama has done everything in its power to avoid dealing with the allegations, including lying to law enforcement.

Anglican Watch is disturbed by Iacopino’s statements, including the potential violation of his Rule 3.3 duty of candor to the tribunal. We also note that civil litigation and Episcopal clergy discipline carry a burden of proof of “preponderance of the evidence,” and hope that “Jack” will investigate both options.

As to Losch’s future, Anglican Watch encourages all parents, caregivers, and other responsible parties to demand that Losch be held accountable by the Episcopal Church.

Moreover, while we cannot prove it, we strongly believe that Losch has victimized others. We encourage anyone in that situation, or anyone with additional information, to contact law enforcement. We also welcome leads, tips, and other information and will treat all such information as confidential.

As for the Episcopal Church and its handling of this matter, the church’s conduct has been abysmal. Indeed, the response has ranged from defeaning silence, to passing the back, to cover-up, to providing false information to law enforcement. At no point has anyone in the denomination alerted the public to the allegations, encouraged other victims to come forward, or fulfilled their legal obligation as mandated reporters.

Episcopal Church officials who have failed to act with integrity in this matter include:

- Then-Presiding Bishop Michael Curry

- Bishop for Pastoral Development Todd Ousley

- Title IV Intake Officer for Bishops Barb Kempf

- President of the House of Deputies Julia Alaya Harris

- National Youth Ministry Officer Canon Myra B. Garnes

- Safe Church Manager Bronwyn Skov

- Assistant to the Presiding Bishop Sharon Jones

- Bishop of Alabama, Glenda Curry

- Alabama Title IV Intake Officer Rob Morpeth

- Executive Assistant to Massachusetts Bishop Alan Gates, Laura Simons

- Diocese of Massachusetts Alan Gates

- Diocese of Massachusetts Title IV Intake Officer Starr Anderson

- Disciplinary Board for Bishops President Bishop Nick Knisely

- Presiding Bishop Sean Rowe

- Presiding Bishop Delegate Herman “Holly” Hollerith

Further, the Episcopal Church ignored pleas to address the matter from an ECLA bishop and the ELCA legal department.

Thus, we have no words to adequately describe the corruption and organizational narcissism the Episcopal Church has displayed in this matter. Indeed, at every level, the denomination has shown itself to be what Jesus described as a “whitewashed tomb, pretty on the outside, while reeking of filth and corruption on the inside,” and a “brood of vipers.”

This Lent, the Episcopal Church has some serious soul-searching to do in light of its egregious corruption, including its unwillingness to address child sexual abuse.

Indeed, there is no evidence to suggest that the denomination even understands why its behavior is wrong, which is both telling and profoundly damning.

YES! I am so disappointed in the Episcopal Church! I have been sent a restraining order via a church attorney. The document is slanderous and full of lies. If you would like to talk to me or read the horrible e-mails that I have been sent from my church, I will share the information and talk to you! Our Rector has been in our church ten years, he begins the process by verbally abusing the church member, then you are asked to leave the church! I have never seen such inhumane behavior in my life!

Please be in touch—we’re happy to do anything we can.

[email protected]

Another lie Michael Lacopino told the jury is that “Jack” was not believable because he described an “out-of-body experience” which is not supported by science. The scientific terms for an “out of body experience” are depersonalization and derealization. Depersonalization is a well documented and robustly studied symptom of PTSD (see the attached article from the US. Department of Veterans affairs web site.) Even the most evil among us like Richard Losch are entitled to legal representation but it should be done ethically.

Dissociative Subtype of PTSD

Ruth Lanius, MD, PhD, Mark Miller, PhD, Erika Wolf, PhD, Bethany Brand, PhD, Paul Frewen, PhD, Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, & David Spiegel, MD

The role of dissociation as the most direct defense against overwhelming traumatic experience was first documented in the seminal work of Pierre Janet. Recent research evaluating the relationship between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and dissociation has suggested that there is a dissociative subtype of PTSD, defined primarily by symptoms of derealization (i.e., feeling as if the world is not real) and depersonalization (i.e., feeling as if oneself is not real).

Continuing Education Course

Dissociative Subtype of PTSD

This course describes a defense cascade model of dissociation to illustrate the etiology and mechanisms underlying symptomatology.

View Course

In This Article

Rationale

Evidence

Assessment

Associated features and risks of the dissociative subtype

Treatment concerns

References

Confrontation with overwhelming experience from which actual escape is not possible, such as childhood abuse, torture, as well as war trauma challenges the individual to find an escape from the external environment as well as their internal distress and arousal when no escape is possible. States of depersonalization and derealization provide striking examples of how consciousness can be altered to accommodate overwhelming experience that allows the person to continue functioning under fierce conditions.

An ‘out-of-body’ or depersonalization experience during which individuals often see themselves observing their own body from above has the capacity to create the perception that ‘this is not happening to me’ and is typically accompanied by an attenuation of the emotional experience.

Similarly, states of derealization during which individuals experience that ‘things are not real; it is just a dream’ create the perception that ‘this is not really happening to me’ and are often associated with the experience of decreased emotional intensity.

The addition of a dissociative subtype to the PTSD diagnosis is expected to further advance research examining the etiology, epidemiology, neurobiology, and treatment response of this subtype and facilitate the search for biomarkers of PTSD.

Rationale

The recognition of a dissociative subtype of PTSD as part of the DSM-5 PTSD diagnosis was based on three converging lines of research: (1) symptom assessments, (2) treatment outcomes, and (3) psychobiological studies. Â Even though dissociative symptoms such as flashbacks and psychogenic amnesia are included as part of the core PTSD symptoms, evidence suggests that a subgroup of PTSD patients exhibits additional symptoms of dissociation, including depersonalization and derealization, thus warranting a subtype of PTSD specifically focusing on these two symptoms. Recognizing a dissociative subtype of PTSD has the potential to improve the assessment and treatment outcome of PTSD.

Back to Top

Evidence

The addition of a dissociative subtype of PTSD in DSM-5 was based on these lines of evidence.

Symptoms of depersonalization and derealization

Several studies using latent class, taxometric, epidemiological, and confirmatory factor analyses conducted on PTSD symptom endorsements collected from Veteran and civilian PTSD samples indicated that a subgroup of individuals (roughly 15 – 30%) suffering from PTSD reported symptoms of depersonalization and derealization (1-3). Individuals with the dissociative subtype were more likely: a) to be male, b) have experienced repeated traumatization and early adverse experiences, c) have comorbid psychiatric disorders, and d) evidenced greater suicidality and functional impairment (4). The subtype also replicated cross-culturally.

Neurobiological evidence

Neurobiological evidence suggests depersonalization and derealization responses in PTSD are distinct from re-experiencing/hyperarousal reactivity. Individuals who re-experienced their traumatic memory and showed concomitant psychophysiological hyperarousal exhibited reduced activation in the medial prefrontal- and the rostral anterior cingulate cortex and increased amygdala reactivity. Reliving responses are, therefore, thought to be mediated by failure of prefrontal inhibition or top-down control of limbic regions. In contrast, the group who exhibited symptoms of depersonalization and derealization showed increased activation in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex. Depersonalization/derealization responses are suggested to be mediated by midline prefrontal inhibition of the limbic regions (5,6).

Effects of depersonalization and derealization on treatment response

Early evidence suggests that symptoms of depersonalization and derealization in PTSD are relevant to treatment decisions in PTSD (reviewed in Lanius et al., 2012;5). Individuals with PTSD who exhibited symptoms of depersonalization and derealization tended to respond better to treatments that included cognitive restructuring and skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation in addition to exposure-based therapies (7,8). Additional research is needed to more fully evaluate the effects of depersonalization and derealization on treatment response.

Back to Top

Assessment

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) includes items assessing depersonalization (“Have there been times when you felt as if you were outside of your body, watching yourself as if you were another person?”) and derealization (“Have there been times when things going on around you seemed unreal or very strange and unfamiliar?”). In addition, there are several self-report rating scales that assess dissociative symptomatology. These include the Dissociative Experiences Scale, the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory, the Traumatic Dissociation Scale, and the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire. Additional interviews and scales specific to the dissociative subtype are currently under development.

Back to Top

Associated Features and Risks of the Dissociative Subtype

As compared to individuals with PTSD alone, patients with a diagnosis of the dissociative subtype of PTSD showed:

Repeated traumatization and early adverse experience prior to onset of PTSD

Increased psychiatric comorbidity, in particular specific phobia and borderline and avoidant personality disorders among women, but not men

Increased functional impairment

Increased suicidality (including suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts)

Back to Top

Treatment Concerns

Treatment studies specifically designed to examine clinical outcomes of psychological and pharmacological treatment of PTSD in those with versus without the dissociative subtype are needed. However, we do know that individuals with dissociative PTSD may require treatments designed to directly reduce depersonalization and derealization. For such individuals, exposure treatment can lead to further dissociation and inhibition of affective response, rather than the goal of cognitive behavioral/exposure therapy, which is desensitization and cognitive restructuring.

There is preliminary evidence that relative to exposure-based therapies alone, individuals with PTSD who exhibited symptoms of depersonalization and derealization responded better to treatments that also included cognitive restructuring and skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation (5,7,8).

AUTHOR NOTE: Dr. Ruth Lanius is a Professor of Psychiatry at Western University of Canada; Drs. Mark Miller and Erika Wolf are Psychologists at the National Center for PTSD at VA Boston Healthcare System; Dr. Bethany Brand is a Professor of Psychology at Towson University; Dr. Paul Frewen is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Western University of Canada; Dr. Eric Vermetten is the Head of Research Military Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center and Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience in Utrecht; Dr. David Spiegel is Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University.

Back to Top

References

Steuwe, C., Lanius, R. A., & Frewen, P. A. (2012). The role of dissociation in civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for a dissociative subtype by latent class and confirmatory factor analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 689-700. doi: 10.1002/da.21944

Wolf, E. J., Lunney, C. A., Miller, M. W., Resick, P. A., Friedman, M. J., & Schnurr, P. P. (2012). The dissociative subtype of PTSD: A replication and extension. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 679-688. doi: 10.1002/da.21946

Wolf, E. J., Miller, M. W., Reardon, A. F., Ryabchenko, K. A., Castillo, D., & Freund, R. (2012). A latent class analysis of dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for a dissociative subtype. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 698-705. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1574

Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., Friedman, M. J., Hill, E., McLaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, C., Spiegel, D., Borges, G., Bunting, B., Calsa-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Demyttenaere, K., Florescu, S., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Kovess-Masfety, V., Lee, S., Matshinger, H., Mladenova, M., Posada-Villa, J., Tachimori, H., Viana, M. C., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the world mental health surveys., 73, 302-312. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022

Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A., & Spiegel, D. (2012). The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 1-8. doi: 10.1002/da.21889

Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R. J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C., Bremner, J. D., & Spiegel, D. (2010). Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 640-647. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168

Cloitre, M., Petkova, E., Wang, J., & Lu Lassell, F. (2012). An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 709-717. doi: 10.1002/da.21920

Resick, P. A., Suvak, M. K., Johnides, B. D., Mitchell, K. S., & Iverson, K. M. (2012). The impact of dissociation on PTSD treatme

Thank you for this.

While we generally steer clear of going to court, we are absolutely willing to testify on “Jack’s” behalf if and when the case is retried. Specifically, we have seen zero evidence of bias on his part, being egged on by anyone (us included), or being incentivized by money. And yes, we understand traveling to NH may be expensive and logistically difficult, but we feel strongly about this case and the need to do what’s right.

Additionally, we are profoundly ashamed of the Episcopal Church’s corruption in this matter.

~Eric Bonetti

Editor